Surprise: These are the most valuable car companies in the world

Among the 10 most valuable car companies in the world are three companies that some people may not even know about. Two of them have not yet sold 1,000 cars together, but are already worth as much as Ford or VW. The automotive industry is analyzing what’s behind it.

Surprise: These are the most valuable car companies in the world

Rivian is the name of the next new star in the automotive sky. The American start-up produces – how could it be otherwise – electric cars. Recently (early November) they celebrated a spectacular debut on the New York Stock Exchange. The company is now worth the equivalent of around 100 billion euros, making it one of the most valuable car manufacturers in the world. Rivian is currently worth practically the same as the venerable Daimler Group, and at times the start-up was even worth more than the entire VW Group.

“No names” are shaking up the industry

The latter generated sales of 222 billion euros in 2020 with around 660,000 employees and delivered 9,305,372 vehicles worldwide. Rivian, on the other hand, only delivered the first pieces in September and reports that there are just 55,000 pre-orders. Founded in 2009 by Robert “RJ” Scaringe The company employs around 9,000 people, posted a billion-dollar loss in 2020 and only has two models on offer: an - admittedly very steep - pickup and an SUV that is scheduled to come onto the market in December. Rivian has also developed an electric delivery vehicle with Amazon, which is also one of the largest shareholders. Amazon has already ordered 100,000 of these vehicles.

Overall, the numbers are comparatively modest - even if you take into account massive expected growth: Rivian wants to increase production to 150,000 vehicles per year by the end of 2023 and is aiming for a million vehicles by the end of the decade. Compared to multinationals like VW or Ford (also an investor in Rivian), the US start-up is still a dwarf. And even Daimler, with 2.84 million vehicles sold worldwide in 2020, was already almost three times as big as Rivian wants to be in 2030.

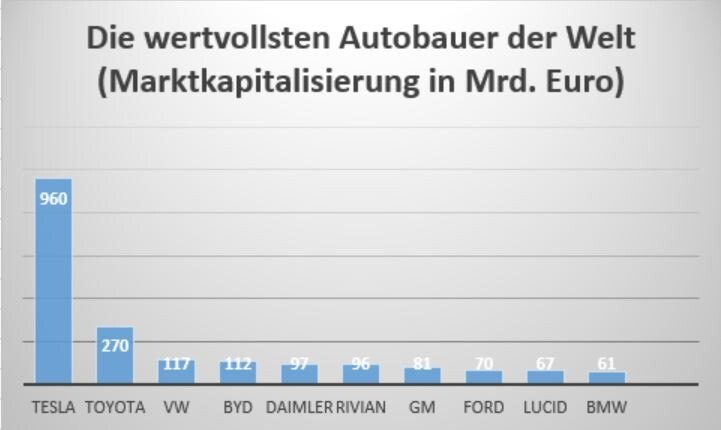

In addition to Rivian, there are other newcomers shaking up the industry: The automotive industry researched the current market capitalization of car manufacturers and found that, in addition to Rivian, Lucid and BYD are also among the top 10. Lucid is certainly comparable to Rivian: The American company was founded in 2015 and has just launched its Air sedan, with further models expected to follow by 2030. This is already worth more to investors than BMW - the market capitalization is close to that of the famous Ford Group. The latter sold more than four million cars worldwide in 2020, and Lucid is confident that it will be able to sell 20,000 cars in the coming year.

Chinese giant

The story behind BYD (the name stands for “Build your dreams”) is, however, different: BYD is a huge technology group that is, among other things, the world leader in battery production and is already one of the largest automobile producers in China. The high market capitalization is not surprising here: the group already has considerable size and market power, but at the same time it is still recording impressive growth rates and a lot of other imagination (not least with affordable electric cars on the western markets). In 2020, sales increased by 22.6 percent to the equivalent of around 20.3 billion euros, and profits even climbed by 162.3 percent to around 550 million euros.

And then of course there is Tesla, also quite a newcomer, which is of course far ahead of its US competitors and is already making nice profits, but is still a dwarf compared to traditional top dogs like VW. However, the group is already worth more than a trillion US dollars (960 billion euros), more than three times as much as the industry's number two, Toyota (see graphic). Now one can argue about whether Tesla is really worth that much, but there is a good reason why the company is valued differently than traditional car manufacturers. Like we did in one a few months ago analysis As we have discovered, Tesla is not a normal car manufacturer, but a technology company with a lot of growth fantasy.

The group also produces batteries and could open up additional sources of income with high profit margins in the future with services and software offerings in the area of autonomous vehicles, GPS services or performance upgrades. There is also the issue of big data – collected data can be used in a variety of ways. In all of these areas, Tesla is years ahead of traditional automakers. They just have to reinvent themselves.

Their core competence, the development and production of combustion engines, is no longer in demand; instead, they have to buy in external know-how in the software sector and sometimes cooperate with large tech giants. The change goes far beyond drive technology.

Innovator’s dilemma

In 1995, Clayton Christensen, a Harvard professor, presented a theory that explains why established companies fail at some innovations and new leaders emerge. In it he argues that certain innovations, the so-called disruptive innovations, can pose a threat to established companies.

Disruptive innovations represent a new technology that lies outside the know-how of established companies and which has the potential to replace the established company's current technology. The company is then faced with the decision of either withdrawing resources from the current technology and investing in the new technology, or waiting to see whether the new technology really becomes established on the market. The former could cause the incumbent to waste resources if the new technology does not catch on, and the latter could cause the company to fall behind technologically if the new technology does catch on. Both can lead to a loss of market share and Christensen describes this situation as the “Innovator’s Dilemma” (which is also the name of his long-legendary book) for established companies.

Since it is initially not foreseeable whether such an innovation will become established at all, it often competes with companies' existing products, and established companies are usually large, cumbersome organizational units, they find it difficult and often miss out on disruptive innovations. This is all the more true since disruptive technologies are initially usually inferior to established products, as Christensen explains. For example, flash memory initially had little advantage over classic hard drives in terms of capacity, reliability and price. But over time they got better and better.

Challengers, often newly founded start-up companies, on the other hand, have nothing to lose and can fully focus on the new technology. This is exactly where names like Tesla, Rivian and Lucid come into play in the automotive industry. Disruptive innovations are new products or services that radially change existing structures or even entire markets. Stock marketers are speculating that something like this is now happening in the auto industry.

Examples from other industries are still well remembered: Nokia was the undisputed world market leader in mobile phones and quickly disappeared after the invention of the smartphone. This should be a warning example to VW and Co. Back then, too, it was thought for a long time that the billion-dollar company would turn things around, but even a strategic alliance with Microsoft was unsuccessful, so the cell phone division was sold in 2013. Other examples include the jump from analogue photography to digital photography, to which the billion-dollar company Kodak ultimately fell victim, or - more recently - the emergence of streaming services. Anyone who invested in Netflix early on could become rich. All of this explains why stocks like Rivian and Lucid are trading so high. Whether they actually deserve the current values remains to be seen.

By the way: There is also a reason why Toyota sells a similar number of cars as VW, but is worth more than twice as much as the Wolfsburg company: VW is a huge conglomerate with a major shareholder called Lower Saxony, who pursues political interests. All of this is punished with discounts on the stock market. In addition, VW traditionally has lower margins than the Japanese. Added to this is the damage to the company's image caused by the diesel scandal.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto