Battery cells: The growth market on your doorstep

The herd of investors is, if you will, moving upstream: Europe has long been left out of the production of battery cells for electric cars. But now you're suddenly the hot spot. The world needs 2,000 gigawatt hours of additional capacity by 2030.

Battery cells: The growth market on your doorstep

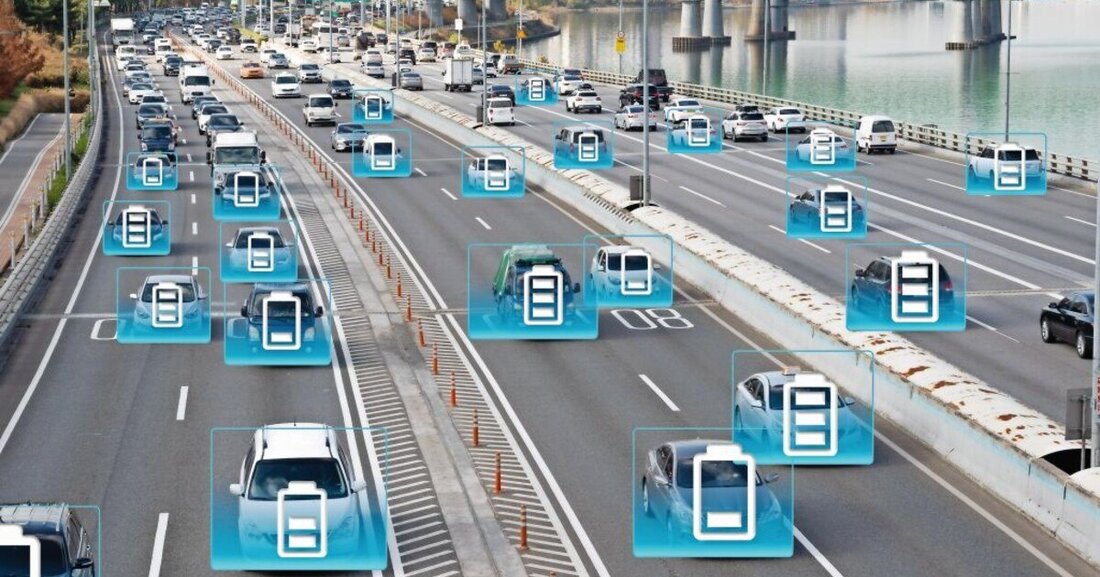

The automotive industry, like many other industries, is experiencing difficult times during the Corona crisis. However, it is precisely at this point in time that one area is experiencing a real boom. We're talking about electromobility. Pushed by climate change and sometimes strict political requirements to reduce CO2 emissions, more and more manufacturers now want to be at the forefront of e-mobility.

The heart of modern electric cars is the battery. The necessary high-voltage batteries are usually based on lithium-ion cells. They account for around 40 percent of the added value of a modern electric car. A huge growth market is opening up here - one in which Asian corporations have so far outpaced the Europeans. In 2019, according to a market analysis, around 90 percent of production capacity was accounted for by manufacturers from the Far East, primarily Chinese companies such as CATL or BYD, followed by LG or Samsung in South Korea and the Japanese group Panasonic. That should change in the future.

Rapid growth

Wolfgang Bernhart, partner at Roland Berger in Stuttgart, has been observing the development for years. He currently puts the global capacity of cells manufactured annually at around 300 gigawatt hours (GWh). By 2030, he estimates, this will increase to 2,300 to 2,500 gigawatt hours, roughly eightfold. From today's perspective, there is a capacity requirement of no less than 2,000 GWh.

$150 billion

According to Bernhart, around 150 billion US dollars will have to be invested for this. Europe will secure a healthy piece of the pie. Individual players have just started producing here; Bernhart estimates the current production capacity to be around 30 gigawatt hours, i.e. just ten percent of the aforementioned 300 GWh produced worldwide. Until recently there were much fewer.

However, the EU's already announced production capacity for 2030 is an impressive 600 GWh (according to Bernhart, this is enough for around ten million vehicles). That would be around a quarter of the global market, making Europe the second largest production location in the world. This is the result of a current analysis by Roland Berger. “New players are coming to Europe, not least because there are attractive subsidies here,” says Bernhart in an interview with the automotive industry. There is also a trend towards regionalization and local value creation. “Europe will be the strongest growth market for the production of battery cells,” emphasizes the expert.

Thousands of new jobs

The EU Commission wants to support research and development of European battery cells with 3.2 billion euros. You don't want to be dependent solely on deliveries from Asia; car companies can also differentiate themselves from the competition through the quality of the energy storage devices. The German Economics Minister Peter Altmaier announced last year: "In the field of battery cell production, thousands of new jobs will be created in Germany over the next few years. By the end of the decade there will be tens of thousands. We must become leaders in this area."

The Swedish company Northvolt, which also runs a joint venture with VW, is currently expanding its Polish site in Gdansk into Europe's largest factory for energy storage solutions. Of course, investors from overseas, such as Chinese companies or Tesla, also want to access European funding.

And setting up and expanding production facilities alone is not enough, as Roland Berger expert Bernhart emphasizes: “It will be a challenge to ensure the entire supply chain, including building up the preliminary capacities and the required raw materials.” Finding qualified engineers is also a challenge. “They are poached from each other,” says Bernhart. The cell assembly itself is highly automated, but someone has to start up the plants eventually. And then the quality has to be right and of course the costs too. The latter would decrease with the number of units, but also through the transition to significantly larger cells. Larger cells and their direct integration into the battery pack (“cell-to-pack technology”) or chassis (“cell-to-chassis technology”) not only reduce costs, but also further increase the energy that can be stored in a space.

80 percent in ten minutes

The latter not only makes the large battery packs unnecessary, but also the individual modules in which the battery cells were previously combined. The bulky, heavy housings in the underbody would be eliminated. The same applies to new developments in cell chemistry, where nickel-rich materials or lithium iron phosphate are used. And from 2025, solid electrolytes will replace liquid materials. All of these developments mean that the batteries are being further optimized.

Bernhart expects that a range of more than 500 kilometers will be standard by 2030. More would be possible, but not economically because it would be more expensive and heavier and generally not necessary. There will also be quick-charging systems that can reach 80 percent of capacity in less than ten minutes, says the expert. And the charging cycles would then significantly exceed the service life of the vehicles.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto